OPINION: Engagement with China needed

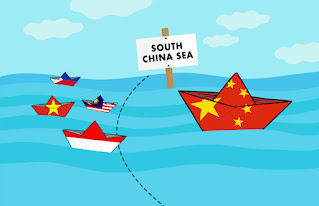

The Jakarta Post - Many recent debates surrounding Indonesia’s supposed leadership in the region have been framed in terms of how Indonesia could (or should) engage China. One of the most heated debates concerns the South China Sea (SCS) issue.

The highly charged tensions in the SCS have cast serious doubts on China’s “peaceful rise”. Recent articles by Evan Laksmana and Klaus Raditio have brought up timely conversations on how best to engage China, to which the author will attempt to contribute.

Whether the term “hegemonic” is deemed as pejorative or neutral, China’s behavior in the SCS ought to be understood through its domestic context. Inability or unwillingness to understand this would seriously undermine our ability to formulate effective policies of engagement.

There are several contributing factors behind China’s behavior that we need to consider. Firstly, is the history factor. China’s claims to the SCS have evolved with its transition from an empire to a modern republic and people’s republic. Different political regimes have made claims and counter-claims throughout its turbulent history. The controversial dashed lines were drawn during the rule of the nationalist regime before they fled to Taiwan and later were adopted by the Communist regime.

The political complications that ensued, especially with regard to the “One China” policy and the unfortunately minimal consultation between the mainland and Taiwan, have not helped in establishing more coherent behavior or less confusing claims.

It is a surprise why public debates tend to be more obsessed against China and to conveniently ignore Taiwan’s rejection to the PCA Ruling and subsequent deployment of naval patrols.

One can argue, because of its sheer size, China is somehow more responsible for the rising tension. However, this lopsided attitude fundamentally undermines the universal respect for international law that most observers have often called upon. Our failure to maintain impartiality can only undermine our role as an “honest broker”.

The second factor is the policy-decision making of institutions. While China retains centralized decision making in fundamental foreign policy issues, day-to-day policy making often involves a lot of players.

Bureaucratic competition between numerous maritime agencies (including functional institutions, local government, security and law enforcement apparatuses, People’s Liberation Army, state-owned enterprises and resource companies) have led to a myriad of initiatives that reflect their different agendas.

This factor is inseparable from the wave of decentralization and the distribution of wealth and power that bloomed since Deng Xiaoping’s “Open Door Policy”.

The more recent One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative has further heightened this phenomenon. After three years, it became more obvious how OBOR-related policy-making processes were not made rigidly top-down as perhaps assumed. It involves thousands of actors from government, security and the private sector taking part in the gradual process of the development agenda. Often times, out of intense competitiveness, some of these actors have resorted to a range of assertive policies and media outbursts.

Unsettled institutional leadership and poor coordination between over a dozen maritime agencies in China have rendered policy making ineffective and prone to interest group agendas. A power struggle that was ignited in 2013 by the central government’s effort to restructure maritime authorities remains unsettled.

Note that this particular problem of (in)effective governance is also something that Indonesia faces after President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo announced the Global Maritime Fulcrum.

We also must remember the massive “bureaucratic reform” instigated by President Xi Jinping’s anticorruption crusade, where hundreds of thousands of officials were indicted these past few years. Institutional readjustments that China should undergo are no small measures and cannot be done instantly.

This is not to condone China’s recent more “erratic” style in diplomacy, or the continued unilateral development in disputed areas, or the puzzling disinterest in stopping illegal fishing.

It is regrettable to see years of social capital nurtured since the late 1990s being stomped by unnecessary reactions. Attempting to galvanize overseas Chinese support for issues like the SCS, for example, is an inapt diplomatic strategy in a region that has a long, complex and intense history of ethnic relations.

Yet we need to also be fair and be able to look beyond overly-baked reports both in mainstream media or social media, like the SCS or illegal workers, etc. Maintaining the prejudice against China as this scary monolithic entity, whose “hegemonic actions” come from straight-from-the-top orders, would be more detrimental than useful.

Beside the need to be less prejudiced, more importantly, it is within our interests to soberly identify key agencies in China as counterparts.

These are the agencies our relevant institutions can engage with on more institutionalized platforms. There have to be institutional adjustments to follow up President Jokowi and President Xi Jinping’s joint statement that highlighted the agreement to synergize Indonesia’s Global Maritime Fulcrum and China’s Maritime Silk Road.

It could be by establishing an umbrella institution, like the National Security Council, as mentioned by Laksmana; or a more Indonesia-China specific institution; or revamp existing institutions, like the Coordinating Ministries. This grand task obviously merits further rational discussions.

Komentar

Posting Komentar